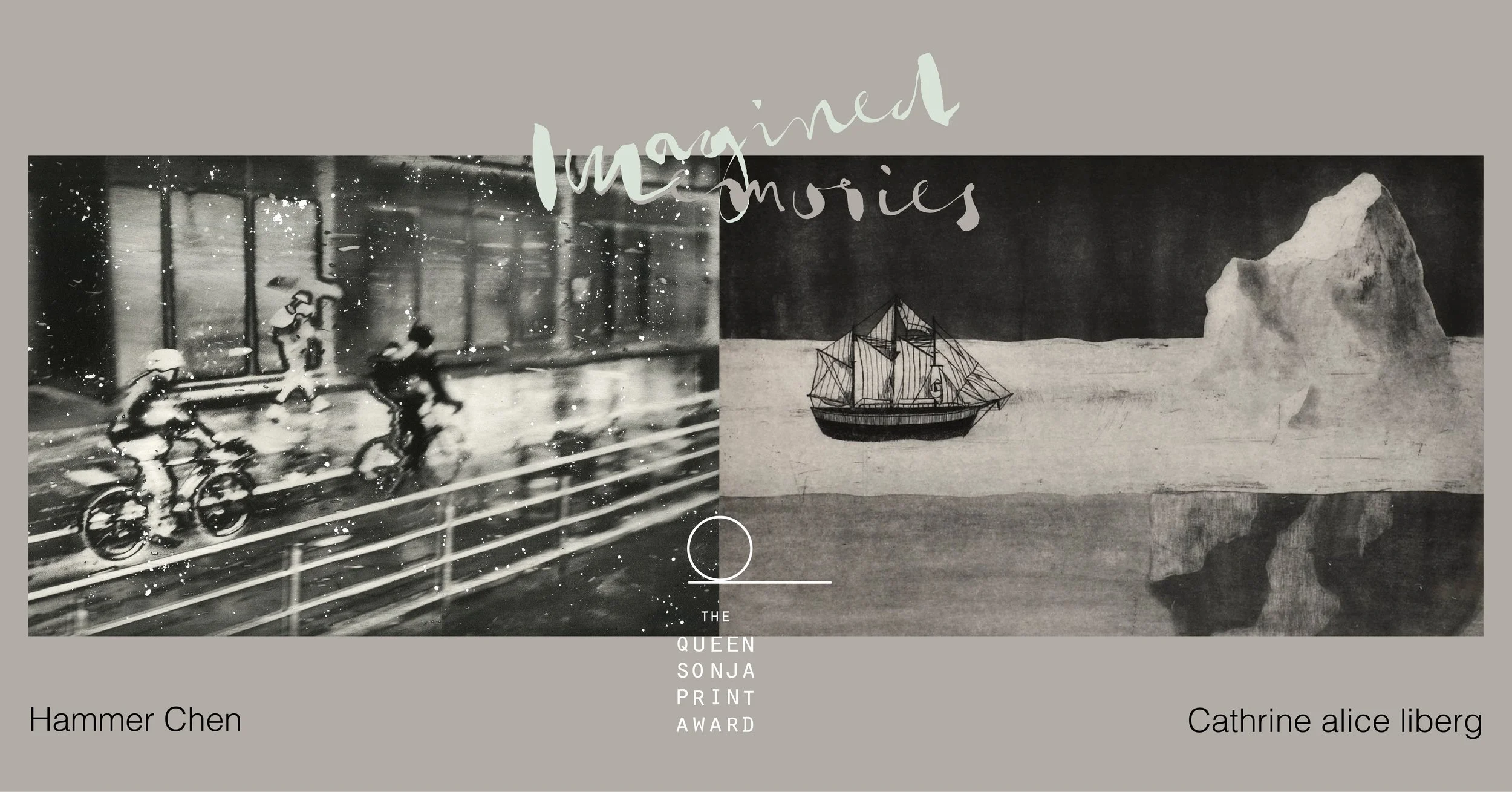

Imagined Memories

-

(b. 1989, China)

is a multi-disciplinary printmaking artist based in Shanghai, China, and Bristol, UK. She graduated from the University of Arts London in 2016 and was honoured with the RE Gwen May Recent Graduate Award by the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers. 2017 following her return to China, Hammer established the “Wait and Roll Printmaking Studio” in Shanghai. In 2023, she completed her Multi-Disciplinary Printmaking MA at UWE Bristol. She was recently honoured with the Creativity Award from The Royal West of England Academy and the Bainbridge Print Prize from the Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair.

-

(b. 1988, Norway)

is an artist and printmaker. In 2019 she received her MFA from the Oslo National Academy of Fine Arts. That same year, she was the recipient of the KoMask European Masters Printmaking Award in Antwerp. Referring to her own Norwegian-Singaporean family background, themes of migration and historical trade routes have long formed the basis of Liberg’s practice. She is particularly interested in the loss of memory and cultural understanding that occurs between generations as a result of migration and diaspora, and how personal family histories can represent fragments of larger global narratives of trade, colonialism and women’s roles. Liberg works with traditional graphic techniques such as lithography, etching, copper engraving and mezzotint.

8th February - 29th March

I lost my memory during a snowboarding trip some ten years ago—a recurring incident in Korean dramas I’ve never watched.

No one would believe that I’m from the mountain because there was no hospital there, and the emergency station didn’t have an O&G department. But my first memory did lead me back to a slope… No, the very first memory was the whiteness. Then I saw my shadow gradually appear on the snow. It was sliding down, following some ski tracks, so I registered that I was moving too, with a certain speed. What connected me to the shadow was my banana-yellow snowboard. My memory of these dozens of seconds must have been intact, and unquestionably my own, since there wasn’t a single soul I knew there to recount it to me afterwards. But once I reached the bottom and met the first person that I knew I knew, my head started to fuck me up again—but at least now I knew the whiteness wasn’t really my first memory, which meant that, after all, I am not from the mountain.

— (Whiteness, Snacks 026, May 2016)

It was just a minor concussion and I’m totally fine now, keeping an hour-to-hour diary to safeguard my marbles—otherwise, absolutely normal. I learned the hard way not to trust memory. Others might linger longer in the illusion of what-I-remember-is-the-truth, but eventually, we all have to struggle.

Some are more stubborn than others, like Hammer, who will spend days manipulating an image on a metal plate, bringing reality captured by a camera closer to what she remembers. Once you see the results, you’ll understand she’s right. Just as the dry, drab description in my diary of every single chore I undertake in a day, most pictures on our phones won’t bring back the excitement of those magic moments that made us press the red virtual button in the first place. That’s why I’ve almost stopped taking pictures at all.

I have many excuses for many things.

“Galaxy bus” once reminded a viewer of the Dutch poem Afsluitdijk by M. Vasalis, which Hammer read on the stage of the Bergen International Literary Festival. (That’s how you sneak a visual art panel talk into a literary festival)

The bus drives through the darkness like a room,

…

There is no tomorrow, no yesterday,

no start or end to this long trip,

just one extended present – strangely split.

(translated by David Colmer)

Cathrine’s ARTICA Svalbard residency journals were much more riveting than my dementia-prevention measure. Already in her first week far up in the north, she realised that “it is impossible to come to Svalbard and not feel that it is going to influence you in some way.”

The thirteen-week-long excursion into the frozen frontier, polar sanctuary—whatever you may call it (how would I know, sitting cosily in my 18-degree climate-controlled studio at home?)—which she considered a rite of passage, took her away from her inward journey into her own diasporic family background through printmaking and towards a broader thematic approach.

The most compelling works are the Terra Nullius; all the failed attempts without surviving witnesses became legends, filling the garish plot holes in expedition history. What is left are the traces gradually unveiled under the melting ice and despondent newspaper headlines that usually end with unanswered question marks.

A cheeky comparison to my own accident on the icy snow—what happened exactly at that moment was anybody’s guess.

In Ted Chiang’s scientific short story The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling, the author interwove two storylines—one personal and one historical—to question how technology-enhanced memory devices, be it a supercomputing lifelog intended to replace our natural memory, or the introduction of writing to an African tribe that, until that moment, had been passing down history from lips to ears.

The duo-exhibition follows, loosely if not tenuously, the same structure—to juxtapose two kinds of imagined memories: the personal but shared, and the collective but highly fictional.

Ben wenhou Yu / 08/02/2025