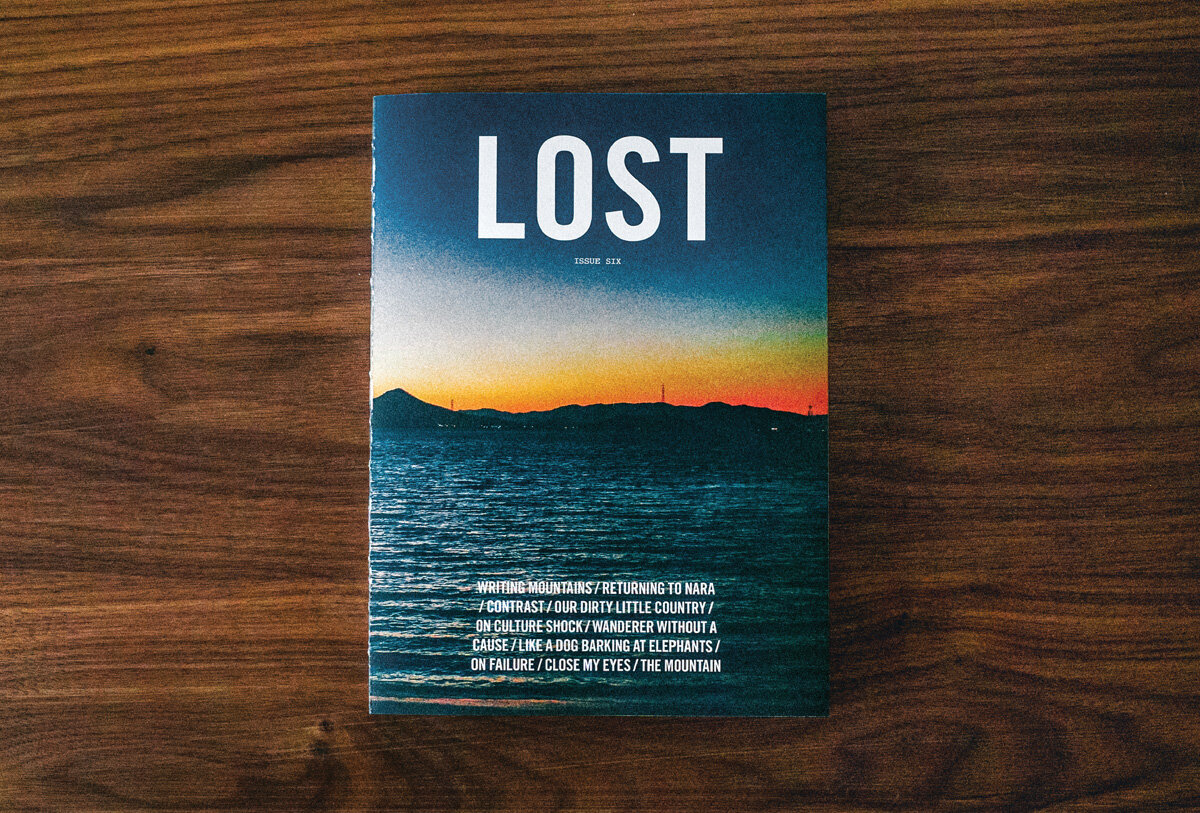

te issue 3: Mirroring 镜中寻步

Much in our life at this moment is often marked by an absence of clarity. Many have experienced a malaise and come to know its persistence. We seem to have become used to stasis and theoretical discussions, lingering in silence and hoping from time to time for something extraordinary to happen. Yet it might also have been a blessing; an opportunity to free ourselves from overarching narratives, to direct our attention to the individual, the local, and to subjects that have long been part of our own lives—a more agile, intuitive mindset. The third issue of te magazine took shape in this context, and chose to confront experiences of “plight”—plight of the persecuted, of the artists, of the forgotten, and of those living with colonial legacies. How might we, as individuals, transmute plights in order to learn to live in this world? If each piece in this issue can be said to propose a mode of healing, the aim is not only about specific pathologies, but rather to recommend adjustments and defenses in moments of crisis. While writing on the plights of others, the authors also look inward for the roots of questions that they have long harbored about their own experiences. As introduced by Jacques Lacan, the theory of “the mirror stage” refers to children's initial awareness of their own existence. As adults, we continue to grapple with the process of self-discovery and understanding, at times feeling trapped deeply in the “mirror.” This issue’s theme, Mirroring represents a continuous exploration of the self. On the one hand, these pieces document the processes of setbacks, negating, questioning and reconciling; on the other, delineate the self through the other, a process discernible in several jointly-authored pieces in this issue, where a special connection and sense of fellowship formed through dialogue, correspondence, and collaborative research. In Siddhartha, Hermann Hesse described how the protagonist's worldview was shaped through seeking and struggle, and we hear in it an echo of the inspiration behind this issue of te: “But now, his liberated eyes stayed on this side, he saw and became aware of the visible, sought to be at home in this world, did not search for the true essence, did not aim at a world beyond.” - Siddhartha by H. Hesse, translated by Hilda Rosner, Bantam Books,1971.

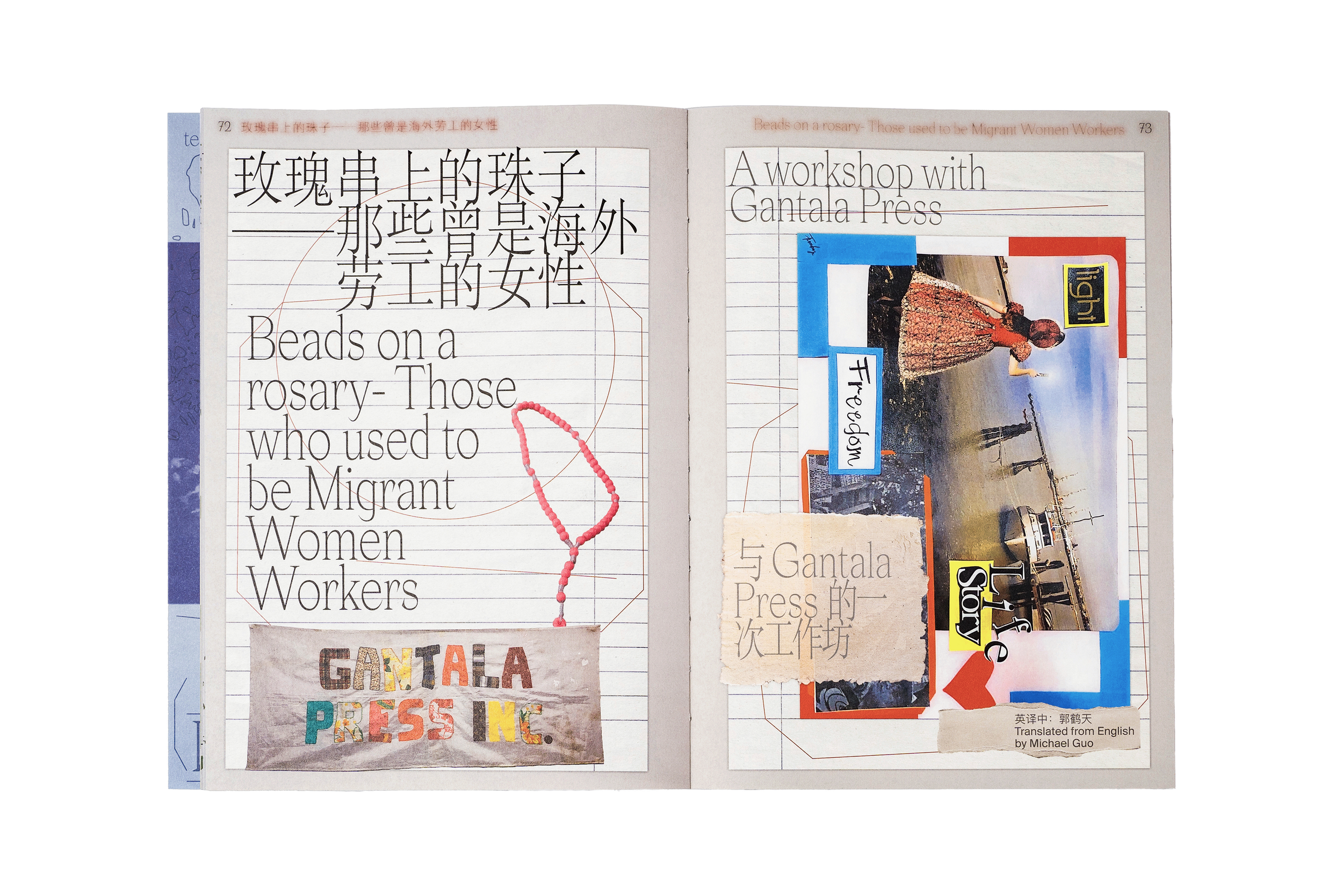

Salvadoran American artist Guadalupe Maravilla uses sound baths as a form of healing. He was sent to the U.S. as an undocumented child to escape the Salvadoran Civil War and has battled cancer. Guadalupe formed a magical bond with Mexican poet and artist Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola through multiple joint creations. Their conversation here revolves around Guadalupe’s new work Mariposa Relámpago, a bus sculpture filled with more than 500 potent objects that the artist collected throughout his journey, and retraces his childhood memories. The conversation’s ebb and flow is driven by incidental discoveries interlaced with the hidden threads of Mariposa Relámpago. Lucía’s poem Notes on Performative Drift, its form modeled on archeological notes, also weaves its way through the piece, and becomes an independent performance. Artists Lee Kai-Chung and Shen Jun made multiple research trips into Northeast Asia along its rail routes. Their piece comprises several short episodes: in a frozen town, at scarcely populated borders, in once busy but long abandoned industrial zones. What’s left of the land and its people after unverbalized traumas accumulated through colonial encounters, economic upheavals, and political movements? What has history left for individuals? Lee and Shen see their research trips as a form of healing, fostering cross-temporal empathy through documenting individual plights and recording scenes of life with a filmmaker’s gaze. Kader Attia examines the impact of colonialism and modern capitalism on traditional societal patterns and individuals in his piece Making Oases: Towards a Collective Individuation. By diving into Algeria’s colonial experience, he highlights the importance of recovering suppressed history and advocates for collective individuation—seeking solidarity and cooperation while maintaining individual identities. Attia proposes an idea of “oasis” formation, the building of spaces for individual aspirations and healing. The piece uses Algeria as a case study, showing us how we might preserve cultural diversity in the face of globalizing forces, thereby facilitating healing for societies and individuals alike. Female migrant workers from the Philippines are an often neglected group. During the pandemic, the structure of their employment was variously impacted, and as a result many of them chose to return home to start a new yet challenging chapter in their lives. Together with the Filipina feminist publisher Gantala Press, we organized a workshop, during which five laborers who had sought employment abroad spoke about their journeys, sharing the keepsakes they took with them when leaving home or the music they enjoyed. The workshop participants took up the medium of collage to give form to emotions born out of their experiences, finding comfort as they shared and created with each other. While political depression isn’t a new term, it hasn’t been widely studied. Scholar Peng Jen-Yu has held therapy sessions with “comfort women” and victims of “The White Terror.” She is skilled in creating environments, for example through family visits or workshops, where the experience of historical traumas is expressed in words. We tasked anthropologist An Mengzhu with interviewing Ms. Peng, in order to learn from her experience as a leading practitioner in the field. What are the ways in which people verbalize pain and trauma in East Asian societies? An important question emerged from the interview: how should we, as non-experts, understand, help and be with those who have experienced and are still living with trauma? Concrete, specific communication strategies may be precisely what many of us need.

The next two pieces unfold along different axes, but express a similar sense of disorientation and feeling adrift. Chang Yuchen’s essay was prompted by a recent trip to Peru and the sense of disconnection from everyday life she has felt since. In the form of a travel log, she reflects on the value system of contemporary life, discusses exoticism and colonialism, and imagines the possibilities for a different kind of existence. Observations from Peru interweave with descriptions of feelings of alienation in New York, where the author currently lives. Chris Zhongtian Yuan’s Intimate Labor is at once a piece of performative creative writing. The protagonist in Chris’s narrative embarks on a journey where a complex emotional experience draws out memories of childhood, family, work environments, and society. The author uses the performances of artist Andrea Fraser and popular culture as a blueprint to interrogate the protagonist’s dilemmas, leading to a self-analysis of the emotional entanglements, confusions, and doubts brought about by the art world and the architecture industry. The protagonist is forced to confront a world where reality and ideals coexist. All of this serves as the author’s schizophrenic analysis of the power dynamics within institutional structures. Chu Yun attempts to shed the identity of “the author” by becoming “the viewer.” Here he describes an asymmetry in the experience of viewing and being viewed, and points to an unbridgeable distance that separates the author and the viewer, the self and the other—a universal sense of solitude. He thinks of author-centered theories as an abstract categorization, a principle on which contemporary art rests and operates. “Viewer photography,” as conceived by Chu, relies on genuine and specific experiences, where the “passivity” of the viewer becomes a starting point for the exploration of the broader meaning of authorship. A series of epistolary exchanges between artist Chen Zhe and astrologer Wu Kun starts with Chen telling Wu about a dream and asking for the latter’s thoughts. Wu explains that the aim of astrology is not to predict the future, but to offer guidance in tough moments. In the second round of exchanges, the relationship between the individual and fate becomes a focal point. Chen confesses that “becoming yourself ” is where she sees the meaning of life reside, while Wu believes the fate of each individual is constantly evolving but ultimately predestined. Together they explore the interplay between fate and individual choice, and how one might locate individual purpose if the direction of life is preordained. Their correspondence continues beyond these pages. Lieko Shiga moved her studio to the small town of Kitagama and took on the role of a community photographer, taking part in local festivities as well as documenting the everyday lives of village residents. Yet the tsunami irreversibly changed these lives. People had to move from damaged homes to temporary shelters; Family photo albums soaked by seawater sat in warehouses awaiting retrieval by their original owners—they became the medium through which people hold onto their life stories. This piece incorporates journal entries by Shiga on living through the tsunami and its aftermath, photos of daily life in Kitagama, and the photography series Spiral Shore. In Shiga’s writing, we see the raw, unmediated response of people faced with brute natural forces. How might photography, as both a repository of memory and a creative expression grounded in social reality, affect the way people experience these events?

—

Format: 18.5 x 26 cm

Pages: 188

Language: Chinese & English

Binding: Hectograph, thread-bound

ISBN: 978-1-80377-097-0

Year: 2024

Contributors: Guadalupe Maravilla, Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola, Kader Attia, Gantala Press, Peng Jen-Yu, An Mengzhu, Chang Yuchen, Chris Zhongtian Yuan, Chu Yun, Chen Zhe, Lieko Shiga

Designer: Can Yang

Design Assistant: Yang Sun

Much in our life at this moment is often marked by an absence of clarity. Many have experienced a malaise and come to know its persistence. We seem to have become used to stasis and theoretical discussions, lingering in silence and hoping from time to time for something extraordinary to happen. Yet it might also have been a blessing; an opportunity to free ourselves from overarching narratives, to direct our attention to the individual, the local, and to subjects that have long been part of our own lives—a more agile, intuitive mindset. The third issue of te magazine took shape in this context, and chose to confront experiences of “plight”—plight of the persecuted, of the artists, of the forgotten, and of those living with colonial legacies. How might we, as individuals, transmute plights in order to learn to live in this world? If each piece in this issue can be said to propose a mode of healing, the aim is not only about specific pathologies, but rather to recommend adjustments and defenses in moments of crisis. While writing on the plights of others, the authors also look inward for the roots of questions that they have long harbored about their own experiences. As introduced by Jacques Lacan, the theory of “the mirror stage” refers to children's initial awareness of their own existence. As adults, we continue to grapple with the process of self-discovery and understanding, at times feeling trapped deeply in the “mirror.” This issue’s theme, Mirroring represents a continuous exploration of the self. On the one hand, these pieces document the processes of setbacks, negating, questioning and reconciling; on the other, delineate the self through the other, a process discernible in several jointly-authored pieces in this issue, where a special connection and sense of fellowship formed through dialogue, correspondence, and collaborative research. In Siddhartha, Hermann Hesse described how the protagonist's worldview was shaped through seeking and struggle, and we hear in it an echo of the inspiration behind this issue of te: “But now, his liberated eyes stayed on this side, he saw and became aware of the visible, sought to be at home in this world, did not search for the true essence, did not aim at a world beyond.” - Siddhartha by H. Hesse, translated by Hilda Rosner, Bantam Books,1971.

Salvadoran American artist Guadalupe Maravilla uses sound baths as a form of healing. He was sent to the U.S. as an undocumented child to escape the Salvadoran Civil War and has battled cancer. Guadalupe formed a magical bond with Mexican poet and artist Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola through multiple joint creations. Their conversation here revolves around Guadalupe’s new work Mariposa Relámpago, a bus sculpture filled with more than 500 potent objects that the artist collected throughout his journey, and retraces his childhood memories. The conversation’s ebb and flow is driven by incidental discoveries interlaced with the hidden threads of Mariposa Relámpago. Lucía’s poem Notes on Performative Drift, its form modeled on archeological notes, also weaves its way through the piece, and becomes an independent performance. Artists Lee Kai-Chung and Shen Jun made multiple research trips into Northeast Asia along its rail routes. Their piece comprises several short episodes: in a frozen town, at scarcely populated borders, in once busy but long abandoned industrial zones. What’s left of the land and its people after unverbalized traumas accumulated through colonial encounters, economic upheavals, and political movements? What has history left for individuals? Lee and Shen see their research trips as a form of healing, fostering cross-temporal empathy through documenting individual plights and recording scenes of life with a filmmaker’s gaze. Kader Attia examines the impact of colonialism and modern capitalism on traditional societal patterns and individuals in his piece Making Oases: Towards a Collective Individuation. By diving into Algeria’s colonial experience, he highlights the importance of recovering suppressed history and advocates for collective individuation—seeking solidarity and cooperation while maintaining individual identities. Attia proposes an idea of “oasis” formation, the building of spaces for individual aspirations and healing. The piece uses Algeria as a case study, showing us how we might preserve cultural diversity in the face of globalizing forces, thereby facilitating healing for societies and individuals alike. Female migrant workers from the Philippines are an often neglected group. During the pandemic, the structure of their employment was variously impacted, and as a result many of them chose to return home to start a new yet challenging chapter in their lives. Together with the Filipina feminist publisher Gantala Press, we organized a workshop, during which five laborers who had sought employment abroad spoke about their journeys, sharing the keepsakes they took with them when leaving home or the music they enjoyed. The workshop participants took up the medium of collage to give form to emotions born out of their experiences, finding comfort as they shared and created with each other. While political depression isn’t a new term, it hasn’t been widely studied. Scholar Peng Jen-Yu has held therapy sessions with “comfort women” and victims of “The White Terror.” She is skilled in creating environments, for example through family visits or workshops, where the experience of historical traumas is expressed in words. We tasked anthropologist An Mengzhu with interviewing Ms. Peng, in order to learn from her experience as a leading practitioner in the field. What are the ways in which people verbalize pain and trauma in East Asian societies? An important question emerged from the interview: how should we, as non-experts, understand, help and be with those who have experienced and are still living with trauma? Concrete, specific communication strategies may be precisely what many of us need.

The next two pieces unfold along different axes, but express a similar sense of disorientation and feeling adrift. Chang Yuchen’s essay was prompted by a recent trip to Peru and the sense of disconnection from everyday life she has felt since. In the form of a travel log, she reflects on the value system of contemporary life, discusses exoticism and colonialism, and imagines the possibilities for a different kind of existence. Observations from Peru interweave with descriptions of feelings of alienation in New York, where the author currently lives. Chris Zhongtian Yuan’s Intimate Labor is at once a piece of performative creative writing. The protagonist in Chris’s narrative embarks on a journey where a complex emotional experience draws out memories of childhood, family, work environments, and society. The author uses the performances of artist Andrea Fraser and popular culture as a blueprint to interrogate the protagonist’s dilemmas, leading to a self-analysis of the emotional entanglements, confusions, and doubts brought about by the art world and the architecture industry. The protagonist is forced to confront a world where reality and ideals coexist. All of this serves as the author’s schizophrenic analysis of the power dynamics within institutional structures. Chu Yun attempts to shed the identity of “the author” by becoming “the viewer.” Here he describes an asymmetry in the experience of viewing and being viewed, and points to an unbridgeable distance that separates the author and the viewer, the self and the other—a universal sense of solitude. He thinks of author-centered theories as an abstract categorization, a principle on which contemporary art rests and operates. “Viewer photography,” as conceived by Chu, relies on genuine and specific experiences, where the “passivity” of the viewer becomes a starting point for the exploration of the broader meaning of authorship. A series of epistolary exchanges between artist Chen Zhe and astrologer Wu Kun starts with Chen telling Wu about a dream and asking for the latter’s thoughts. Wu explains that the aim of astrology is not to predict the future, but to offer guidance in tough moments. In the second round of exchanges, the relationship between the individual and fate becomes a focal point. Chen confesses that “becoming yourself ” is where she sees the meaning of life reside, while Wu believes the fate of each individual is constantly evolving but ultimately predestined. Together they explore the interplay between fate and individual choice, and how one might locate individual purpose if the direction of life is preordained. Their correspondence continues beyond these pages. Lieko Shiga moved her studio to the small town of Kitagama and took on the role of a community photographer, taking part in local festivities as well as documenting the everyday lives of village residents. Yet the tsunami irreversibly changed these lives. People had to move from damaged homes to temporary shelters; Family photo albums soaked by seawater sat in warehouses awaiting retrieval by their original owners—they became the medium through which people hold onto their life stories. This piece incorporates journal entries by Shiga on living through the tsunami and its aftermath, photos of daily life in Kitagama, and the photography series Spiral Shore. In Shiga’s writing, we see the raw, unmediated response of people faced with brute natural forces. How might photography, as both a repository of memory and a creative expression grounded in social reality, affect the way people experience these events?

—

Format: 18.5 x 26 cm

Pages: 188

Language: Chinese & English

Binding: Hectograph, thread-bound

ISBN: 978-1-80377-097-0

Year: 2024

Contributors: Guadalupe Maravilla, Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola, Kader Attia, Gantala Press, Peng Jen-Yu, An Mengzhu, Chang Yuchen, Chris Zhongtian Yuan, Chu Yun, Chen Zhe, Lieko Shiga

Designer: Can Yang

Design Assistant: Yang Sun

Much in our life at this moment is often marked by an absence of clarity. Many have experienced a malaise and come to know its persistence. We seem to have become used to stasis and theoretical discussions, lingering in silence and hoping from time to time for something extraordinary to happen. Yet it might also have been a blessing; an opportunity to free ourselves from overarching narratives, to direct our attention to the individual, the local, and to subjects that have long been part of our own lives—a more agile, intuitive mindset. The third issue of te magazine took shape in this context, and chose to confront experiences of “plight”—plight of the persecuted, of the artists, of the forgotten, and of those living with colonial legacies. How might we, as individuals, transmute plights in order to learn to live in this world? If each piece in this issue can be said to propose a mode of healing, the aim is not only about specific pathologies, but rather to recommend adjustments and defenses in moments of crisis. While writing on the plights of others, the authors also look inward for the roots of questions that they have long harbored about their own experiences. As introduced by Jacques Lacan, the theory of “the mirror stage” refers to children's initial awareness of their own existence. As adults, we continue to grapple with the process of self-discovery and understanding, at times feeling trapped deeply in the “mirror.” This issue’s theme, Mirroring represents a continuous exploration of the self. On the one hand, these pieces document the processes of setbacks, negating, questioning and reconciling; on the other, delineate the self through the other, a process discernible in several jointly-authored pieces in this issue, where a special connection and sense of fellowship formed through dialogue, correspondence, and collaborative research. In Siddhartha, Hermann Hesse described how the protagonist's worldview was shaped through seeking and struggle, and we hear in it an echo of the inspiration behind this issue of te: “But now, his liberated eyes stayed on this side, he saw and became aware of the visible, sought to be at home in this world, did not search for the true essence, did not aim at a world beyond.” - Siddhartha by H. Hesse, translated by Hilda Rosner, Bantam Books,1971.

Salvadoran American artist Guadalupe Maravilla uses sound baths as a form of healing. He was sent to the U.S. as an undocumented child to escape the Salvadoran Civil War and has battled cancer. Guadalupe formed a magical bond with Mexican poet and artist Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola through multiple joint creations. Their conversation here revolves around Guadalupe’s new work Mariposa Relámpago, a bus sculpture filled with more than 500 potent objects that the artist collected throughout his journey, and retraces his childhood memories. The conversation’s ebb and flow is driven by incidental discoveries interlaced with the hidden threads of Mariposa Relámpago. Lucía’s poem Notes on Performative Drift, its form modeled on archeological notes, also weaves its way through the piece, and becomes an independent performance. Artists Lee Kai-Chung and Shen Jun made multiple research trips into Northeast Asia along its rail routes. Their piece comprises several short episodes: in a frozen town, at scarcely populated borders, in once busy but long abandoned industrial zones. What’s left of the land and its people after unverbalized traumas accumulated through colonial encounters, economic upheavals, and political movements? What has history left for individuals? Lee and Shen see their research trips as a form of healing, fostering cross-temporal empathy through documenting individual plights and recording scenes of life with a filmmaker’s gaze. Kader Attia examines the impact of colonialism and modern capitalism on traditional societal patterns and individuals in his piece Making Oases: Towards a Collective Individuation. By diving into Algeria’s colonial experience, he highlights the importance of recovering suppressed history and advocates for collective individuation—seeking solidarity and cooperation while maintaining individual identities. Attia proposes an idea of “oasis” formation, the building of spaces for individual aspirations and healing. The piece uses Algeria as a case study, showing us how we might preserve cultural diversity in the face of globalizing forces, thereby facilitating healing for societies and individuals alike. Female migrant workers from the Philippines are an often neglected group. During the pandemic, the structure of their employment was variously impacted, and as a result many of them chose to return home to start a new yet challenging chapter in their lives. Together with the Filipina feminist publisher Gantala Press, we organized a workshop, during which five laborers who had sought employment abroad spoke about their journeys, sharing the keepsakes they took with them when leaving home or the music they enjoyed. The workshop participants took up the medium of collage to give form to emotions born out of their experiences, finding comfort as they shared and created with each other. While political depression isn’t a new term, it hasn’t been widely studied. Scholar Peng Jen-Yu has held therapy sessions with “comfort women” and victims of “The White Terror.” She is skilled in creating environments, for example through family visits or workshops, where the experience of historical traumas is expressed in words. We tasked anthropologist An Mengzhu with interviewing Ms. Peng, in order to learn from her experience as a leading practitioner in the field. What are the ways in which people verbalize pain and trauma in East Asian societies? An important question emerged from the interview: how should we, as non-experts, understand, help and be with those who have experienced and are still living with trauma? Concrete, specific communication strategies may be precisely what many of us need.

The next two pieces unfold along different axes, but express a similar sense of disorientation and feeling adrift. Chang Yuchen’s essay was prompted by a recent trip to Peru and the sense of disconnection from everyday life she has felt since. In the form of a travel log, she reflects on the value system of contemporary life, discusses exoticism and colonialism, and imagines the possibilities for a different kind of existence. Observations from Peru interweave with descriptions of feelings of alienation in New York, where the author currently lives. Chris Zhongtian Yuan’s Intimate Labor is at once a piece of performative creative writing. The protagonist in Chris’s narrative embarks on a journey where a complex emotional experience draws out memories of childhood, family, work environments, and society. The author uses the performances of artist Andrea Fraser and popular culture as a blueprint to interrogate the protagonist’s dilemmas, leading to a self-analysis of the emotional entanglements, confusions, and doubts brought about by the art world and the architecture industry. The protagonist is forced to confront a world where reality and ideals coexist. All of this serves as the author’s schizophrenic analysis of the power dynamics within institutional structures. Chu Yun attempts to shed the identity of “the author” by becoming “the viewer.” Here he describes an asymmetry in the experience of viewing and being viewed, and points to an unbridgeable distance that separates the author and the viewer, the self and the other—a universal sense of solitude. He thinks of author-centered theories as an abstract categorization, a principle on which contemporary art rests and operates. “Viewer photography,” as conceived by Chu, relies on genuine and specific experiences, where the “passivity” of the viewer becomes a starting point for the exploration of the broader meaning of authorship. A series of epistolary exchanges between artist Chen Zhe and astrologer Wu Kun starts with Chen telling Wu about a dream and asking for the latter’s thoughts. Wu explains that the aim of astrology is not to predict the future, but to offer guidance in tough moments. In the second round of exchanges, the relationship between the individual and fate becomes a focal point. Chen confesses that “becoming yourself ” is where she sees the meaning of life reside, while Wu believes the fate of each individual is constantly evolving but ultimately predestined. Together they explore the interplay between fate and individual choice, and how one might locate individual purpose if the direction of life is preordained. Their correspondence continues beyond these pages. Lieko Shiga moved her studio to the small town of Kitagama and took on the role of a community photographer, taking part in local festivities as well as documenting the everyday lives of village residents. Yet the tsunami irreversibly changed these lives. People had to move from damaged homes to temporary shelters; Family photo albums soaked by seawater sat in warehouses awaiting retrieval by their original owners—they became the medium through which people hold onto their life stories. This piece incorporates journal entries by Shiga on living through the tsunami and its aftermath, photos of daily life in Kitagama, and the photography series Spiral Shore. In Shiga’s writing, we see the raw, unmediated response of people faced with brute natural forces. How might photography, as both a repository of memory and a creative expression grounded in social reality, affect the way people experience these events?

—

Format: 18.5 x 26 cm

Pages: 188

Language: Chinese & English

Binding: Hectograph, thread-bound

ISBN: 978-1-80377-097-0

Year: 2024

Contributors: Guadalupe Maravilla, Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola, Kader Attia, Gantala Press, Peng Jen-Yu, An Mengzhu, Chang Yuchen, Chris Zhongtian Yuan, Chu Yun, Chen Zhe, Lieko Shiga

Designer: Can Yang

Design Assistant: Yang Sun